Agenda-setting under Algorithm: Constructing and Re-constructing "The Daily Me" in Social Media

- Lilyann Zhao

- 2018年12月28日

- 讀畢需時 13 分鐘

Introduction

In 1995, MIT technology specialist Nicholas Negroponte predicted a new paradigm of news production --"The Daily Me" in his book Being Digital to illustrate the possibility of personalized service in further digital age that news agency could customized for an individual's tastes and users could also have more autonomy to construct their own editorial voice (Negroponte, 1995). In current Web 2.0 era, his hypothesis seems to be gradually realized by algorithmic computational-tools, which could recommend or filter updated contents or services through analyzing individual-related data. This kind of advanced technology could be associated with agenda-setting function of news agency and social media. For instance, Facebook News Feed uses algorithm to provide taste-specific contents to “create users’ own personal newspaper” (Tonkelowitz, 2011).

On the one hand, the emergence of this personalized information service is an inevitable consequence of today’s information overload condition, as well as a new approach of respecting and satisfying users' digital rights (Lan, 2018). On the other hand, there are also many critiques along with this technological process. Many scholars point out users who are used to immerse into this algorithm-created sphere are just like fish in water, which could be easily influenced by impacts of algorithm like filter bubble (Pariser, 2011) and information cocoons (Sunstein, 2006).

This article aims to analysis the relationship between filter bubble and algorithm in the agenda-setting process of social media, mainly including the following three aspects: firstly, a current debate of Facebook News Feed’s hate-speech issue will be discussed. Secondly, the author will analyze deeper on how algorithms construct and reconstruct this "The Daily Me” paradigm with agenda-setting theory related to existing research. Thirdly, several conclusions would be raised based on the impacts of algorithm on users, platforms and social public sphere.

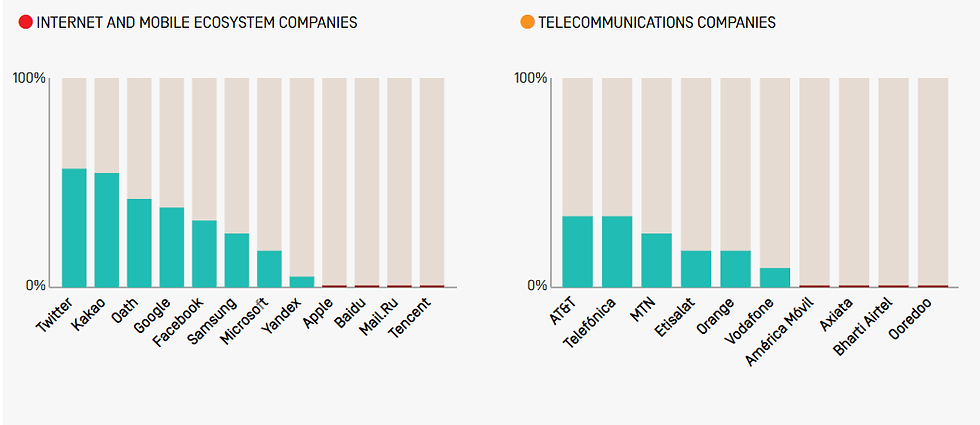

Description: Facebook News Feed Algorithm and German Anti-refugee Violence

Facebook wants to optimize meaningful interactions by adjusting its News Feed algorithm nowadays. On January 11th, 2018, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook News Feed algorithm would be updated to prioritize content from “friends, family and groups” to let users more connective with each other. (Zuckerberg, 2018). However, the specific operation procedure of this algorithm is still in unseen and unknown ways. According to 2018 Corporate Accountability Index published on April 26th, 2018, Facebook received 31 scores in “User notification about content and account restriction”. Researchers argue that, although Facebook “made slight improvements to its disclosure some data on content violating its rules”, it still lacks disclosure of how these Facebook’s algorithms “restrict or remove content in general” (MacKinnon, 2018).

Table 1

User Notification about Content and Account Restriction in Internet and Mobile Ecosystem Companies and Telecommunications Companies

Based on this research result, it seems that Facebook still need to attach importance on the risks of this gradually personalized information service, for instance, it may lead to more isolation instead of “connection” or even bias (Boyd, Levy& Marwick,2014) to some specific events in a user-unconscious way, such as this case below.

On Aug 21, 2018, The New York Times published a report which accused Facebook has led a risky impact on Germany’s spate of anti-refugee violence (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018). In this report, Karsten Müller and Carlo Schwarz at Warwick University scrutinized 3335 anti-refugee attacks in Germany with an astonishing result which showed “Wherever per-person Facebook use rose to one standard deviation above the national average, attacks on refugees increased by about 50 percent.” (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018). Moreover, these researchers also announced that “this effect drove one-tenth of all anti-refugee violence” after they estimated in an interview. Based on this incredible finding, they explored the research deeper.

In one of their interviews in Altena, Anette Wesemann, the owner of Altena’s refugee integration center told the researchers her perspective to refugees “changed immediately” when she set up one Facebook page for center’s organization, she received flooding anti-refugee posters from Facebook News Feed. Based on this phenomenon, researchers explained, “The links with Facebook to anti-refugee violence would be indirect but the algorithm that Facebook uses truly determines each user’s newsfeed.” (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018). In other words, algorithm, with the key mission of promoting content that will maximize user engagement, keeps updating so-called “the most valuable and relative” information by analyzing users’ personal information, historical search records, reading preferences and so forth, which is the main reason why Anette Wesemann with such digital record of refugee could become the target audience of those refugee-related information. However, Anette Wesemann was not alone under the influence of that algorithmic agenda-setting. Facebook promotes infectious contents through its algorithm to all like-minded groups, which may cause its users convinces that what they saw is the “truth”, or even define themselves as authority. Actually, Facebook News Feed, even all the social media platforms could not be fully capable to show the complete public atmosphere, or “reality” by their personalized recommendation algorithms. What they create is just a “media reality”. Based on that contradiction, filter bubble (Pariser,2011) emerged to describe such “intellectual isolation” nowadays, which will be deeper discussed in next chapter.

In traditional forms, journalists and editors use their professional media literacy to set agenda. Nowadays, algorithms which are often deployed as gatekeeper, is somehow similar or even replace the role of newspaper editor, are used to setting agenda in digital times and to some extent, reconstructing users’ online social space. (Tufekci, 2015)

Before deeper into the analysis, two concepts need to be clarify in advance.

Concept explanation

Agenda-setting theory.

This theory can be traced to the first chapter of Public Opinion, which is written by Walter Lippmann (Lippmann, 1922). In this chapter, he argued that “The world as they needed to know it, and the world as they did know it, were often two quite contradictory things.” (Lippmann, 1922). Although the term "agenda setting" has not been put forward directly in his book, the idea has been conveyed in the first time. After Lippmann, many scholars enriched this theory from their perspective. In 1963, American political scientist Bernard Cohen illustrated that media “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.” (Cohen, 1922). In this process, one notable case related to agenda-setting theory is "Chapel Hill study", while Max McCombs and Donald Shaw compared the salience of political events in news reports with public’s perception of the important election issue in 1968, in order to determine to what extent does media influence public opinion (McCombs& Shaw, 1972). Since this study, more than 400 literatures have been published with the discussion of mass media’s agenda-setting function till 1972.

In general, agenda-setting theory has been described as the "ability of the news media to influence the importance placed on the topics of the public agenda” (McCombs& Reynolds, 2002). In current times, this theory has been innovative applied by social media, which would be deeply discussed in next chapter.

Filter Bubble

It is a term emerged in 2010 by internet activist Eli Pariser to describe a state of “intellectual isolation” (Pariser, 2012). In web2.0 era, algorithms inside social media platforms come to “find us” (Lash, 2006), provide users’ personal contents sorted and filtered by algorithms. In this point, there would be a causal relationship between setting agenda and filter bubble. As it has been mentioned in the case of Facebook’s “anti-refugee violence” (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018) , users seem to be influential by those anti-refugee views and are stuck into their single Facebook-tinged social norms and radicalizing “ideological bubbles” (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018). In 2016, the astonished result of US presidential election also brought constant concern to filter bubble that public paid closer attention in questioning whether this effect brought by algorithm would damage online democracy and users’ digital right.

In the next chapter, these two concepts related to Facebook’s “anti-refugee violence” case (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018) will be both analyzed with existing research to explore the internal logic of algorithmic agenda-setting process and the construction effect to "The Daily me" paradigm. Besides, the importance and social implications of such discourse will be also discussed in this chapter.

Discussion: Who Should Take Charge for “Filter Bubble”?

In this era of personalization, as the case of “Facebook’s anti-refugee violence effect” mentioned before (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018), does algorithmic really have the power to control, instead of mediate users’ information ecosystem in general? Does individual's vision become more and more narrow and polarized, until being reduced to "prisoner" in filter bubbles? There are still some discourses on the power of algorithm among different scholars. Actually, this debate could be valuable for individuals and society, as the author of The Filter Bubble, Eli Pariser spoken, each algorithmic not only presents as one form of technology, but also “contains and show a point of view on the world” (Pariser, 2015). Based on that, the more “we interrogate how these algorithms work and what effects they have, the more we’re able to shape our own information destinies.” (Pariser, 2015). In other words, seeing how “algorithmic culture” (Striphas, 2015) is experienced and how “algorithmic life” is lived (Amoore & Piotukh, 2016) could also help users themselves burst the filter bubble effectively.

Users’ Self-censorship

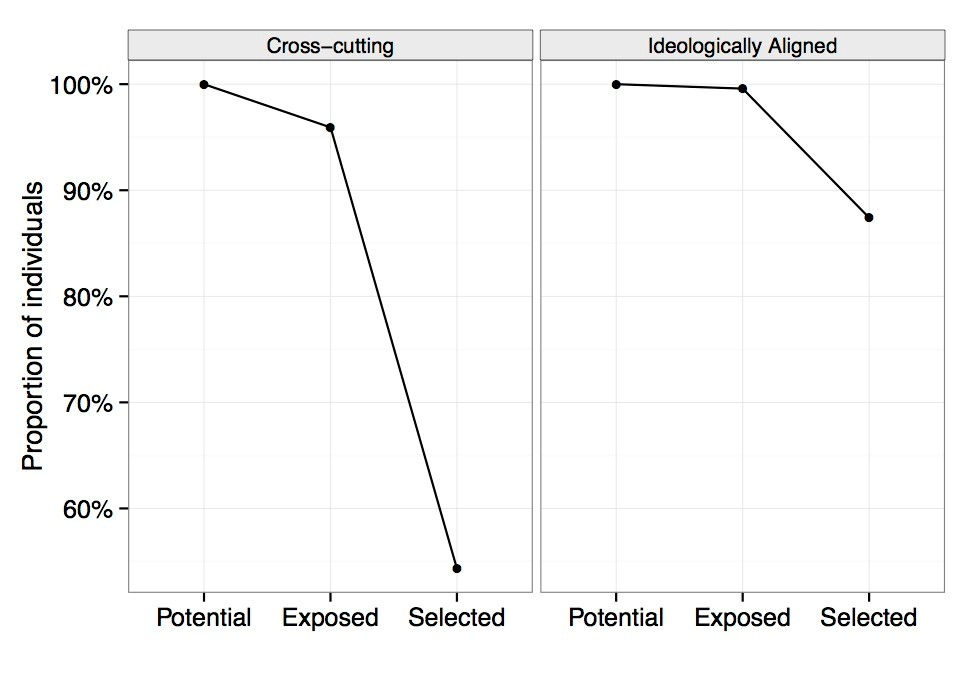

On the one hand, some researchers argue that there is no necessary connection between algorithm and filter bubble, on the contrary, the trend of content convergence are more influenced by self-censorship. In 2015, Facebook has emphasized that “individual choice” plays a more important role on diversity of information than algorithm. Below is one of their data results showing that “99 percent of users were exposed to at least one ideologically aligned item, and 96 percent encountered at least one ideologically cross-cutting item in News Feed.” (Eytan Bakshy, Lada Adamic, Solomon Messing, 2015)

Table 2

Proportion of individuals with at least one cross-cutting and aligned story

(1) shared by friends (potential), (2) actually appearing in peoples’ News Feeds (exposed) (3) clicked on (selected).* (Eytan Bakshy, Lada Adamic, Solomon Messing, 2015)

Moreover, researchers from Oxford University argue that those people who are in the risk of algorithmic control are only about 8% of the population based on their research result. What’s more, users still have enough subjective initiative to use “multiple platforms and media outlets” instead to passively falling in those “filter bubbles”. (Hamill, 2018) Mills Baker argue that former researchers exaggerate the strength of technology, even fall into "technological determinism", which he insists is algorithm does not produce filter bubbles meaningfully , is “our values” create “our own filter bubbles”. Based on that, Mills Baker explains “what persuades users usually reflects a priori determinations of what their values inform them to accept”, which is an urgent problem so far quite beyond those Facebook News Feed algorithms. (Baker, 2016)

Algorithmic Discrimination, Content Invisibility and Net-imperialism

On the other hand, some scholars still regard filter bubbles as “the original sins” of the algorithm (Lan, 2018), mainly discussed the impact of algorithmic discrimination, content invisibility and net-imperialism that could cause users’ filter bubbles.

Firstly, algorithmic discrimination. Boyd, Levy and Marwick argue that algorithms could identify user’s networks, predict their online behavior and then pose new potentials for discrimination and inequitable treatment to users (Boyd, Levy&Marwick,2014). Besides, Joseph Turow pays more attention to “marketing discrimination” (Turow, 2006). Graham, Hayles, Thrift and Turow also demonstrate this term from a similar angle that computer algorithms expedites “automated basis” and the lack of “human discretion” by give taste-specific contents to users (Graham, 2004).

Secondly, content invisibility. Taina Bucher suggests algorithm could pose a threat of invisibility (Bucher, 2012). As John B. Thompson (2005) points out, visibility is fundamentally mediated and affected by the medium itself, Taina Bucher argued that “filter bubble” is actual a form of “personal informational invisibility”, which is not a completely new phenomenon. He also quotes Marshall McLuhan’s famous theory, “the medium is the message” (McLuhan,1964) to demonstrate it is the algorithmic medium that “makes the message visibility and governing visibility in a certain direction” in new media era. Besides, other scholars have similar discussions, such as Taylor suggests that ‘Facebook’s Edge Rank algorithmic holds all power of visibility’ (Taylor ,2011).

Thirdly, net-imperialism. Scholars consider filter bubbles brought by algorithm as a representation of “power movement” (Beer, 2009). In 2007, Scott Lash use “new new media ontology” to describe information has turned to be capable to shape people’s lifestyle (Scott Lash, 2007). Afterwards, Roger Burrows applies Scott Lash’s work to explain information technologies now ‘comprise’ or ‘constitute’ rather ‘mediate’ users’ lives (Burrows, 2007), which can be clearly seen an emphasis of the technologies’ power. MacCormick then explains the power of this algorithm is in its ability to ‘find needles in haystacks’ (MacCormick, 2012). Moreover, some scholars like Nigel Thrift, Katherine Hayles and Steve Graham start from the user's vulnerability, illustrate users tend to sink into a “technological unconscious” (Thrift, 2005) because algorithm nowadays strengths its capacity to structure and reconstruct people’s live in “unseen and concealed ways” (Hayles, 2006). Some scholars try to better analysis this kind of algorithmic net-imperialism from the perspective of platform profit model. Thrift presents the power of algorithm as a form of “cultural circuits of capitalism” (Thrift, 2005) and Taina Bucher argues that the set of Facebook News Feed is not only modelled as “pre-existing cultural assumptions”, but also, more importantly, “geared towards commercial and monetary purposes.” (Bucher, 2012).

In conclusion of this chapter, existing research in the effect of algorithmic could be divided into two main opinions: Some scholars like Bucher, MacCormick and Thrift regard algorithm as the primary cause of filter bubbles in the agenda setting process while others like Eytan Bakshy, Lada Adamic, Solomon Messing argue that filter bubbles have no direct relationship to algorithms, or even filter bubbles do not exist at all.

In fact, these two judgments may both tend to be extreme if those researchers completely separate the user's subjective initiative from the influence of the algorithm, as Lan (2018) suggests, although users’ selective exposure (Katz, 1968) and self-censorship has always existed, it still cannot deny that the current agenda setting from personalized recommendation algorithm will, to some extent, enhance this “selective exposure” and then bring the risk of “filter bubbles” (Pariser, 2011), which may emphasis the exposure of “personalized issues” instead of public agenda (Lan, 2018). However, from the perspective of people's social needs, public communication and public agenda are still necessary. As mentioned above, if everyone merely pays attention to a small area of his interest affected by algorithms, he may be less and less aware of the outside world, which may lead to a lack of a “common perspective”, which means that people's judgments of some facts will be different and consensus is difficult to be integrated when they are immersed into their “filter bubbles”, or the form of “The Daily Me”. (Lan, 2018) Besides, the social integration function of communication should not fade away, whether in the traditional media area or in this “algorithmic era”. The public agenda that can integrate all kinds of people still need to reach the widest population because it is not only an important tool to establish individual’s sense of belonging, but also the link between different social strata and groups. (Lan, 2018)

In this sense, both platform owners and users should be alert to this problem of "filter bubbles" that may be brought about by personalized algorithms. But on the other hand, it should be also realized that if used properly, the algorithm may become a weapon to burst those filter bubbles. For instance, sometimes algorithm needs to provide some harsh voices to let users better understand the multifaceted nature of the real world (Lan, 2018) . Moreover, algorithm should also be designed to keep “neutral” by making those contents with public value reach a wider population by analyzing publicity content.

Conclusion

“Social media is an illusion.” (Amanda.T & Max.F, 2018). Facing with such an “illusion”, it is necessary to have a clear concern in distinguishing the "algorithmic world" and the "real world", instead of unconsciously being manipulated. Through discussing case of the Facebook’s anti-refugee violence in agenda-setting theory, the author of this article goes deeper in how algorithm constructing and re-constructing the form of "The Daily me" in social media by analyzing the relationship between algorithm and its possible effect: filter bubbles. Moreover, as social media is one form of mass media, it should inherit the social integration function of mass media. Based on that, algorithms should also focus on balancing personalized information and public issues, correcting rather than strengthening social prejudices and shift users’ “the Daily Me” into "black box society". (Pasquale, 2015)

Although there are still many obstacles to overcome in order to be truly implemented, in such an era, as data and algorithms become important factors to determine personal life as well as a manifestation of power (Lan, 2018), it could be necessary to arouse more public's attention, not only by identifying these phenomena, but also keeping clear-minded to the logic of internal power relations in those algorithmic processes.

Reference

Amanda, T., & Max, F. (2018, Aug 21). Facebook Fueled Anti-Refugee Attacks in Germany, New Research Suggests. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/21/world/europe/facebook-refugee-attacks-germany.html

Amoore, L., & Piotukh, V. (Eds.). (2016). Algorithmic life: Calculative devices in the age of big data. London: Routledge.

Beer, D. (2009). Power through the algorithm? Participatory web cultures and the technological unconscious. new media & society, 985-1002.

Bucher, T. (2012). Want to be on the top?Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook. new media & society, 1164-1180.

Boyd, D., & Levy, K., & Marwick, A. (2014). The networked nature of algorithmic discrimination. Open Technology Institute. Retrieved from http://www.danah.org/papers/2014/Data Discrimination.pdf

Baker, M. (2016, December 17). Filter Bubbles and Bias on Twitter and Facebook. Retrieved from Medium: https://medium.com/quora-design/filter-bubbles-on-twitter-and-facebook-ebf2b10442be

Cohen, B (1963). The press and foreign policy. New York: Harcourt.

Eytan, B., Lada, A., & Solomon M. (2015, May 7). Exposure to Diverse Information on Facebook. Retrieved from Facebook Research: https://research.fb.com/exposure-to-diverse-information-on-facebook-2/

Graham, S. (2004) ‘The Software-sorted City: Rethinking the “Digital Divide”’, in S. Graham (ed.) The Cybercities Reader, pp. 324–32. London: Routledge

Hamill, J. (2018, February 22). Facebook and Twitter are not creating ‘echo chambers’ and ‘filter bubbles’, academics claim. Retrieved from METRO: https://metro.co.uk/2018/02/22/facebook-twitter-not-creating-echo-chambers-filter-bubbles-academics-claim-7334193/

Hayles, N.K. (2006). ‘Unfinished Work: From Cyborg to the Cognisphere’, Theory,

Culture & Society 23(7–8): 159–66.

Katz, & Elihu. (1968). On reopening the question of selectivity in exposure to mass communication. In Theories of cognitive consistency: A sourcebook. Edited by Robert P. Abelson, et al., 788–796. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Lan, P. (2018). 假象、算法囚徒与权利让渡——数据与算法时代的新风险. Journal of the Northwestern Teachers University, 20-31.

Lash, S. (2007b). ‘New New Media Ontology’, Presentation at Toward a Social Science of Web 2.0, National Science Learning Centre, York, UK, 5 September.

Lippmann, W (1922). Public opinion. New York: Harcourt.

Lash, S. (2006) ‘Dialectic of Information? A Response to Taylor’, Information,

Communication & Society 9(5): 572–81.

McCombs, M; Shaw, D (1972). "The agenda-setting function of mass media". Public Opinion Quarterly. 36 (2): 176. doi:10.1086/267990

McCombs, M; Reynolds, A (2002). "News influence on our pictures of the world". Media effects: Advances in theory and research.

MacCormick, J. (2012). 9 Algorithms that changed the future: The ingenious ideas that drive today’s computers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

MacKinnon, R. (2018, April 26). F8. User notification about content and account restriction. Retrieved from Ranking Digital Rights: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2018/indicators/f8/

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. London: Routledge.

Negroponte, N. (1995). Being Digital. United States: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. New York: Penguin Press.

Pariser, E. (2012). Filter Bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think. New York: New York, N.Y. : Penguin Books.

Pariser, E. (2015, May 7). "Fun facts from the new Facebook filter bubble study". Medium.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black Box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Striphas, T. (2015). Algorithmic culture. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18, 395–412. doi:10.1177/1367549415577392

Sunstein, C. R. (2006). Infotopia:How Many Minds Produce Knowledge. United State: Oxford University Press, USA; 1 edition (July 28, 2006).

Savage, M. and R. Burrows (2007) ‘The Coming Crisis of Empirical Sociology’, Sociology 41(6): 885–99.

Tufekci, Z. (2015). Algorithmic Harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent Challenges of Computational Agency. COLO.TECH.L.J, 203-216.

Taylor, D. (2011). Everything you need to know about Facebook’s EdgeRank. TheNextWeb. Available at: http://thenextweb.com/socialmedia/2011/05/09/everything-you-need-to-knowabout-facebook’s-edgerank (accessed 3 February 2012).

Tonkelowitz, M. (2011). Interesting news, any time you visit. The Facebook Blog. Available at: http://blog.facebook.com/blog.php?post=10150286921207131 (accessed 3 February 2012).

Thrift, N. (2005). Knowing Capitalism. London: SAGE.

Thompson JB. (2005). The new visibility. Theory Culture & Society 22(6): 31–51.

Turow, J. (2006). Niche Envy: Marketing Discrimination in the Digital Age. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Zuckerberg, M. (2018, Jan 1). Facebook. Retrieved from Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104413015393571

留言